Nachträglichkeit (afterwardsness in English, après coup in French) is a term from psychoanalysis. It was the word Freud used for how later events revise the memory of an earlier one and thereby disclose new meaning in it. Memory arises out of this exchange between an earlier and the present self. The moment from which we are looking back brings as much to its creation as the past moment we recall.

Afterwardsness (2022) was published in a limited edition as part of the campaign to commemorate Stefan Zweig’s residence in London from 1933-39. The resulting blue plaque will be unveiled in 2023. Each essay in the collection links England to a different European country and to the world beyond.

The above image shows Seaton Junction, a disused railway station in Devon. The future George Orwell, aged seventeen, accidentally became separated there from a school group and embarked upon his ‘first adventure as an amateur tramp.’ The essay in ‘Afterwardsness’ about this first appeared as a pamphlet in 2018. Through Orwell’s writing, especially about nature, it connects England, France and Myanmar.

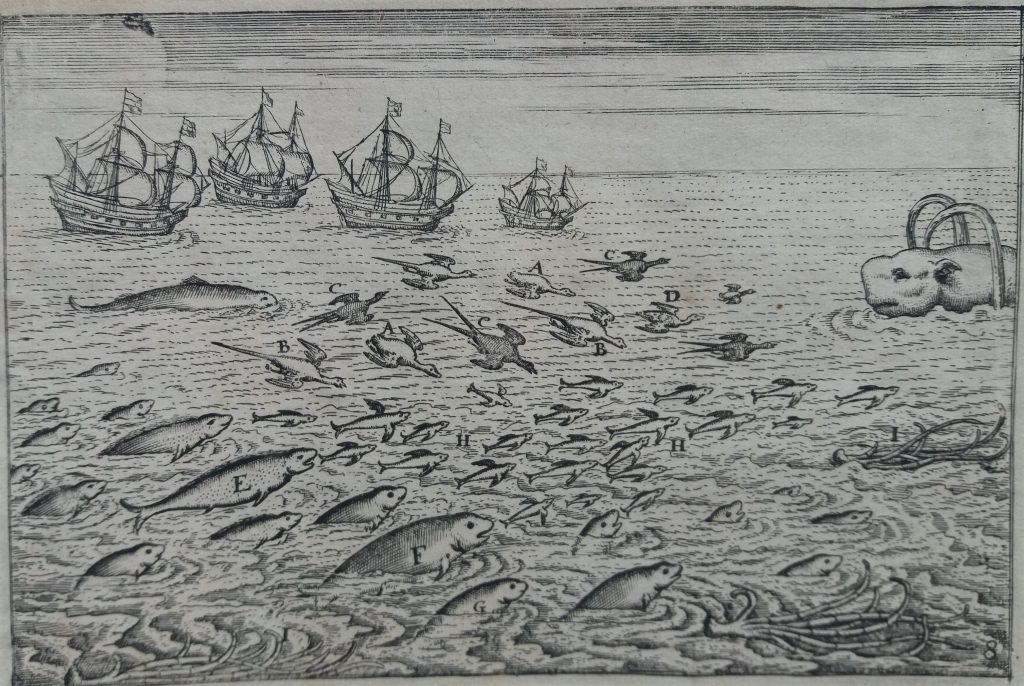

The Paradoxal Compass (2017) examines contradictions in the West Country’s identity. An image of settled rural existence overlaps there with a quite different kind of story, in which the region figures as point of departure for voyages both famous and infamous. As the first English province to globalise, it was implicated from the start in the contradictory nature of that process.

The use of science by 16th c. explorers (many of the English ones grew up in the South West), their motives for setting out, their attitude to the peoples encountered, the close attention they paid to marine wildlife, what it meant to grow up with such stories and what it means to reflect upon them today – all of these are themes running through the book.

I’ve looked again at one of the best-known of those voyages, Drake’s circumnavigation, asking what, if anything, it might say to us now. As Anna Tsing puts it in The Mushroom at the End of the World, ‘Worse yet, we are mixed up in the projects that do us most harm. The diversity that allows us to enter collaborations emerges from histories of extermination, imperialism and all the rest.’

Several of the essays in Lady Chatterley’s Defendant & Other Awkward Customers (2011) explore the role of religion in contemporary life: ‘If I had to explain to a young, thoughtful Muslim, or his evangelical Christian counterpart, why absolute freedom of thought matters to me, I would start with Samuel Butler. The New Atheists wouldn’t get a look-in, and that is not because I am from the Neville Chamberlain School of anything. It’s because I believe that clear, witty, temperate prose, in the service of true imaginative power, is the best persuader we have, and the best persuader we will ever have.’ This is from Samuel Butler, or The Art of Being Funny about Religion, an essay in this volume.